Rare and Unique Cars Found at Hershey

Posted by Jil McIntosh on Nov 28th 2019

Each year, car fans come from across the continent, and often from around the world, to the town of Hershey, Pennsylvania. And for good reason: it’s the site of one of the world’s largest antique-auto flea markets.

Hosted by the Hershey Region of the AACA (Antique Automobile Club of America), it’s been going since 1955. Although the Saturday car show is for unmodified vehicles only, the flea market has just about everything: auto memorabilia, original classic car parts, tools, and even classic parts for rod and custom builders.

What’s really cool are cars from long-defunct companies, some of them dating back to the automobile’s earliest days. Have you ever heard of any of these?

Winton

One of America’s oldest car companies, Winton was founded in 1897 by Alexander Winton, a bicycle manufacturer in Cleveland, Ohio. His first car had a one-cylinder engine, weighed 1,000 pounds, and was a “dos-a-dos,” meaning it had front and rear seats facing away, so passengers sat with their backs to each other.

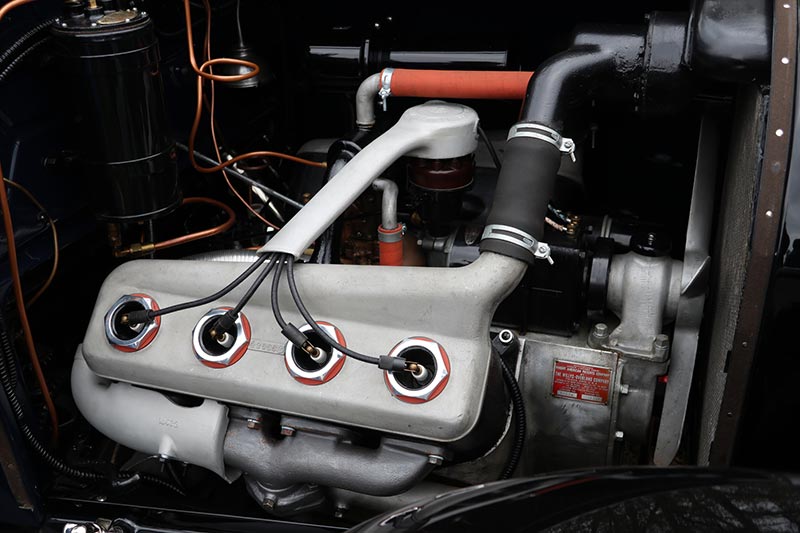

Wintons were big and expensive, and by the time this 1917 touring car was built, all models used six-cylinder engines. The company also made marine engines, and continued to do so after car production ended in 1924. General Motors bought its diesel marine engine business in 1930.

Lambert

In 1891, the Buckeye Manufacturing Company of Anderson, Indiana made a three-wheeled carriage that might have been the first gasoline-powered vehicle built in the U.S. It started making the Lambert in 1904, with a two-cylinder engine and chain drive, and with two- or five-passenger seating.

It was common for early automakers to build their own chassis and bodies, but to buy their engines from suppliers like Continental or Buda. That’s what Lambert did, and its later models used four- or six-cylinder engines. Buckeye stopped building cars in 1917, but made commercial vehicles for two more years after that.

Rambler

You might know the name, but probably not from this far back. Thomas Jeffrey made bicycles in Kenosha, Wisconsin, but sold that business to get into auto manufacturing and turned out his first car in 1902. Rambler was the name of his old bicycle brand. Thomas Jeffrey died in 1910, and four years later, the Rambler became the Jeffrey.

Charles Nash bought the company in 1916, and the following year, the Jeffrey automobile was renamed the Nash. In 1950, Nash brought out a compact model and used the old Rambler name. Nash would later merge with Hudson to form AMC (American Motors Corporation), which for a while used the Rambler name on all its models.

Marmon

Only two American automakers, Cadillac and Marmon, ever offered a V-16 engine. But that masterpiece of a powerplant was still well in the future when Howard Marmon built his first cars in 1902 in Indianapolis, using an air-cooled V-4 engine. Although the cars were big, Marmon was a pioneer in lightweight construction, with extensive use of cast aluminum, even in the seats and chassis, and with aluminum bodies.

Marmon offered only water-cooled engines after 1908, gradually adding six- and eight-cylinder models. The mighty V-16 arrived for 1931, displacing 494 cubic inches (8.1 litres) and making some 200 horsepower. It cost less than a V-16 Cadillac, but was still $5,200 when the most expensive Ford was $640. It had been designed when times were good but came to market during the Depression, and only 390 V-16 models were made. Marmon closed its doors in 1933.

Amphicar

If you can’t make up your mind between a boat or a car, why should you have to choose? Built in Germany from 1961 to 1968, the land-and-sea Amphicar was the brainchild of Hans Trippel, who had worked on amphibious vehicles in the Second World War. It had a rear-mounted, four-cylinder Triumph engine and two small propellers behind the rear wheels. Its rubber door seals were similar to those on refrigerators, and with extra locks to hold them tightly when in water.

Top speed was about 70 mph on land, and 15 mph on water. At $3,031 it was expensive; available options included an anchor and a paddle. It wasn’t a very good car and wasn’t a very good boat, and only about 2,800 were made, but they’re very popular with collectors today.

Brewster

You either think Brewster’s trademark heart-shaped grille is the height of fashion, or the most hideous thing ever put on a car. One thing’s for sure: Brewster-built cars change hands today for some pretty high prices.

The Brewster company was formed twice, starting in 1915 in Long Island, New York. It made bodies for other automakers, and also made cars of its own (with more conventional styling) using engines it bought from a supplier. It made bodies for Rolls-Royce, which briefly built cars in the U.S., and that company bought Brewster in 1925. Nine years later, Brewster reopened in Massachusetts and introduced the heart-grille styling. It didn’t make its own cars anymore but put bodies on chassis from other automakers, primarily Ford and Buick, until 1936. This one pictured is on a 1938 Rolls-Royce.

Franklin

Built from 1901 to 1934, Franklin was considered the world’s most successful air-cooled car until the Beetle came along. Built in Syracuse, New York, the car was advertised through a number of stunts to prove its worth to those who didn’t trust air cooling, including cross-continental drives, and idling for a day in a locked garage in desert heat.

With no need for a radiator, early Franklins had odd-looking front ends. In 1923, the company’s dealers stormed the headquarters and demanded more conventional styling or they’d sell other brands. From then on, Franklin got a fake radiator. Famed aviator Charles Lindbergh was a fan of the car – the equivalent of getting a top movie actor or star athlete to vouch for your product today – and in 1928, Franklin named one its models the Airman in his honor.

Rickenbacker

Eddie Rickenbacker was a race car driver and a fighter pilot in the First World War, and in 1922 “threw his hat in the ring,” as he put it, and got into the auto business with his Detroit-built car. The first models used a six-cylinder engine with two flywheels, which made it extremely smooth-running. Later the company would add an inline eight-cylinder.

Most cars of the day only had brakes on their rear wheels, and Rickenbacker was the first moderately-priced car to add brakes on the front. The car’s logo was an American-flag-themed top hat in a ring and it was everywhere, even cast into hidden places on the chassis and in the glass headlight lenses. Its downfall was that Eddie Rickenbacker wanted to give the average motorist a very high-quality car for a low price, which just wasn’t sustainable. The company closed in 1927.

Orient Buckboard

At the turn of the 20th century, a few manufacturer made “cyclecars.” These were small, lightweight models that bridged the gap between cars and motorcycles. Brands included the Auto Red Bug, Real Cyclecar, Briggs & Stratton Flyer, and Carnation. Inexpensive and low-powered, they were often purchased to use for inner-city trips, or by farmers or estate owners to get around their property.

Built in Waltham, Massachusetts by the aptly-named Waltham Manufacturing Company, the Orient Buckboard was made from 1902 to 1907, with a one-cylinder engine and priced around $375. Toward the end of its run, the company was also making a conventional four-cylinder touring car that cost $3,200.

Hahn

In addition to automakers, there were a lot of smaller and little-known truck companies in the early days, such as Gray, Lange, Urban, and Tower. Hahn was built in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, starting in 1907.

The company made a number of different models, from one-ton and smaller, to a three-quarter ton. It also made fire apparatus, and when it ended its commercial truck production in the 1930s, it continued to supply fire companies right up until 1989.

Thorne

Based in Chicago, Thorne built trucks from about 1929 until 1938. It specialized in walk-in trucks for route distribution, such as home delivery of milk or bread. But while you may think hybrids are new, Thorne was using the technology way back in the day, as were a few other delivery-van companies that were working with electric motors.

Thorne used a gasoline engine, but instead of being hooked to a transmission, it powered a generator attached to the back of it. In turn, the generator fed an electric motor on the rear differential. The engine used less fuel than powering the rear wheels directly, but the big benefit was that the driver only had to pull a brake lever at each stop, instead of using the clutch and shifting gears to get to the next house.

Graham

The three Graham brothers – Ray, Robert, and Joseph – started out with a glass factory, which they sold and which became Libbey-Owens-Ford. Then they formed a truck body company and, in 1921, agreed to build trucks under their name for Dodge, sold by Dodge dealers and using that automaker’s drivetrains. Dodge eventually bought a majority of the company. Chrysler bought Dodge in 1928, and two years later, Graham Brothers Trucks became Dodge Trucks.

But in 1927 the Graham brothers had bought Paige, a Detroit-based car company, and started making cars. It was successful for quite a while, although radical new styling in 1938 – called “Spirit of Motion” by the company, although the public dubbed it “shark-nose” – wasn’t a hit with buyers. That, plus an expensive failed attempt to build a car called the Hollywood with tooling from the defunct Cord automobile, ended production in 1941. After the Second World War, Graham-Paige was acquired by Joseph Frazer, who built his own car and then merged into Kaiser-Frazer.

Little

While most companies were started by men who first invented a car and then tried to sell it, General Motors was founded by William “Billy” Durant, who bought existing companies to put under his GM umbrella. When he bought too many unsuccessful brands, his directors booted him out. He then teamed up with race driver Louis Chevrolet to create a new car. He also called on William Little, who’d been a manager at Buick, to make a car for him as well.

Built in Flint, Michigan in 1912 and 1913, the Little was simple and cheap, while the Chevrolet was big and pricey. Durant combined the best of both into one car that could compete with Ford’s Model T. Seeing his name on a lower-priced model was enough for Louis Chevrolet to quit the project, but Chevrolet sold well enough that Durant used it to leverage his way back into the president’s chair at GM.

Knight

This was actually an engine company that licensed its technology to manufacturers, including Britain’s Daimler, France’s Panhard et Levassor, and briefly, Mercedes-Benz. In the United States, it was used in the Willys-Knight, Stearns-Knight, and Falcon-Knight, among others.

A conventional engine uses poppet valves that open and close for fuel and exhaust, and in the early days these were noisy, with a tendency for the valves to burn and for the rudimentary valve springs to break. The Knight was a “sleeve-valve” engine. Two metal sleeves in each cylinder, one inside the other, slid when operated by short connecting rods. Each sleeve had a slot near the top. During each stroke, these slots aligned with the cylinder ports, pulling in fuel or expelling exhaust. The engines were complicated and expensive, and they burned a lot of oil, but they were exceptionally smooth and quiet. Charles Knight patented his design in 1905 and it was used into the 1930s.

Duesenberg

Many auto historians say the greatest American car ever made was the Indianapolis-built Duesenberg. It was created by brothers Fred and August Duesenberg, who first made bicycles, and then marine engines and race cars, before building their first luxury Duesenberg Model A in 1920. They were skilled engineers but not very good at running a company. Their savior was businessman Errett Lobban “E.L.” Cord, who bought the company in 1926 and asked them to create a car that would surpass anything on the road.

The famous Model J of 1929, and the supercharged Model SJ of 1932, did just that. You’d pay $8,500 for the chassis alone, about the price of an average house, but you got a car that, by some accounts, made more than 300 horsepower and a top speed of almost 130 mph. (That was undoubtedly exaggerated, but even half that would have been a big deal in 1932.) Cord’s company also made the Auburn and front-wheel-drive Cord, but weakened by the Depression, all three were gone by 1937.